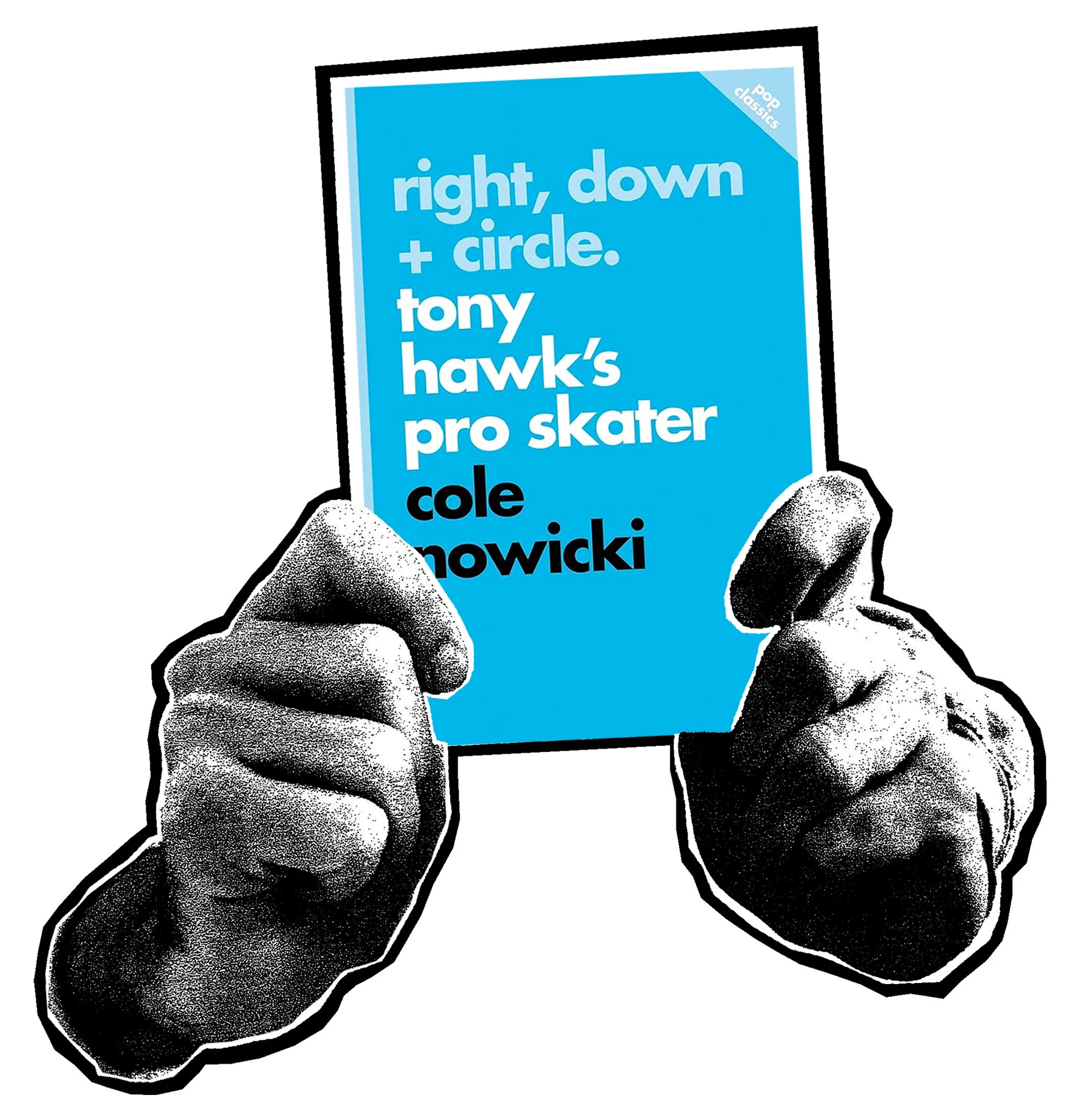

Free Press | Right, Down + Circle: Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater

by Cole Nowicki

To anyone remotely familiar with skateboarding subculture, there are few aspects more synonymous than Tony Hawk’s revered namesake video games. In an attempt to demonstrate the game’s supreme cultural legacy, this concise book sets the stage by investigating the arcade-like titles that proceeded the THPS franchise. The text then takes a deep dive into the pertinent elements of the series, including music choice and character selection. The below excerpt from Chapter 4 examines the crop of individuals whose mastery within the professional ranks simultaneously transformed them into relatable on-screen personas and legendary skateboarding figureheads.

Chapter 4: “Real Skateboarders, Just Pixelated"

Up until the late 1990s, photos and video were the only media of mythmaking in skateboarding, for better or worse. The skateboarding industry essentially created its own media apparatus to do this, with Fausto Vitello and Eric Swenson starting Thrasher Magazine to promote their company Independent Trucks. Subsequently, the lifeblood of every publication was the ad dollars brought in through skateboarding brands, which meant the magazines, in order to sell both copies and advertising, became quite adept at creating heroes out of the skateboarders who represented those brands. Mostly men and mostly white, these professional skaters existed on a separate plane. They even seemed to breathe different air. You, the young fan and skateboarder, were lucky to watch the legends grow in reputation in magazines and on your TV screen.

Occasionally, you'd get a glimpse of their personalities in an interview or some flash of B-roll, but never enough to create a complete human image. Instead, they were but a chalk outline that you could fill with whatever traits suited you and your friend group best. A brilliant, blank, and easily personalized marketing triumph.

And in a culture as young as skateboarding, its initial architects are mostly still alive and able to be worshipped. Venerable skateboarding brand Powell Peralta released their seminal video The Search for Animal Chin in 1987. It immortalized skateboarders like Lance Mountain, Steve Caballero, Mike McGill, and Tony Hawk. A photo taken by J. Grant Brittain during filming of all four upside down on a vert ramp performing inverts in sync, mere inches from one another, is one of skateboarding's most iconic images. It carries such historical weight that the four skaters recreated the photo - on a full recreation of the original "Animal Chin" vert ramp- 30 years later. These four men in bright neon, straining to stay upright, are a cultural touchstone. A large print of the original image hangs near the till of my local burrito joint in Vancouver, BC.

When a camera is pointed in the right direction, these brief moments - the seconds it takes to execute a trick or shoot off a witty one-liner - can make a skateboarder into something more. But, of course, a moment lacks nuance. Another iconic photo, taken by Craig R. Stecyk III in 1975 and featuring a young Jay Adams crouching as he speeds past a pylon in the middle of the street, is what most of his generation, and many that followed, remember about Adams. The grimace as his hand grazes the asphalt, style oozing from the very core of his being - he is skateboarding's original bad boy, a figure so iconic that he was played by Emile Hirsch in the 2005 film Lords of Dogtown. As Stacy Peralta (of Powell Peralta) would tell XGames.com following Adams's death in 2014, "Adams was the purest form of skateboarder that I've ever seen."

In August 1975, Adams was celebrated on the cover of Thrasher. He'd be on it once more in 1989. And yet, people don't often mention that he was charged with murder and convicted of felony assault following the beating death of a gay man in 1982, a gruesome hate crime Adams himself would admit to initiating. The images, like the mythic ones of Jay Adams, lack necessary nuance. Even so, they still wield influence all these decades later.

Late in September 1999, there was an abrupt rewiring of how skateboarding's system of heroes operated, a new dimension added. You could now do more than just look at a professional skateboarder in a magazine or video, you could be them. Tony Hawk's Pro Skater was released for PlayStation, and, suddenly, the young fan and skateboarder could choose from an actual roster of professional skateboarders. From the titular Tony Hawk to

Andrew Reynolds, Kareem Campbell, Bob Burnquist, Chad Muska, Rune Glifberg, Elissa Steamer, Bucky Lasek, Jamie Thomas, or Geoff Rowley. A scattershot collection of some of skateboarding's biggest names of the day.

Andrew Reynolds, who at the time was cementing himself as a generational star (one who'd later be known amongst his contemporaries as "The Boss"), had just released his now-classic video part in Birdhouse Skateboards' feature-length The End, frontside-kickflipping his place into history. Kareem Campbell's smooth brand of street skating had previously been showcased in World Industries' videos New World Order, 20 Shot Sequence, and Trilogy, already placing him in the company of legends. Chad Muska was as close to a superstar as skateboarding had at that moment, the Shorty's Skateboards pro was as adept at marketing his personality as he was at skating.

Florida's Elissa Steamer, the beloved Toy Machine rider who'd made a name for herself in the company's videos Welcome to Hell and Jump off a Building, was already a pioneer of women's skateboarding by the time Neversoft came calling. Geoff Rowley came to the United States from Liverpool in 1994 with little money or regard for his own health and safety. Within a few weeks, he was on the cover of Transworld Skateboarding.

Then there were the game's vert skaters: Bob Burnquist, a Brazilian phenom; the hyper-technical Dane, Rune Glifberg, and Americans Bucky Lasek and Tony Hawk rounded out the roster's surprisingly robust vert contingent. This wildly talented bunch occupied a strange space within the profession, sometimes considered verifiable legends while, at other times, irrelevant relics once skateboarders took to the streets following the industry's last bust period in the '8os. "Vert button" became a common term for pressing fast forward whenever a vert skater's section started playing in a video. Despite a drop in status within skate culture, vert eventually found a new life on commercial network television following the debut of the X Games in 1995. Vert skaters began scooping up endorsement deals and raising their O rating with the general public, even if that didn't often translate to popularity with core skate-boarders. And now, here was an opportunity to become a character in a video game.

Excerpted and adapted from Right, Down + Circle: Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater by Cole Nowicki. © 2023 by Cole Nowicki.

All rights reserved. Published by ECW Press Ltd. www.ecwpress.com

Photos: Chloe Krause

Originally published in Issue 2 - January 2024